about the mindfulness institute for emerging adults

We’re on a mission to empower emerging adults with a life-changing mindfulness program.

Leading the Way in Mindfulness for Higher Education

Our proven success, evidence-based curriculum, innovative approach, and unwavering commitment have made us the go-to source for over 200 campuses worldwide.

Decades of Experience with Emerging Adults

At the Mindfulness Institute for Emerging Adults, our co-founders, Holly Rogers, MD and Libby Webb, MSW, each spent over two decades working in Duke University’s student counseling services, developing expertise in the mental health needs of emerging adults.

Photo: Students practicing mindfulness with MIEA co-founder Holly Rogers while waiting for tickets to a Duke Basketball game.

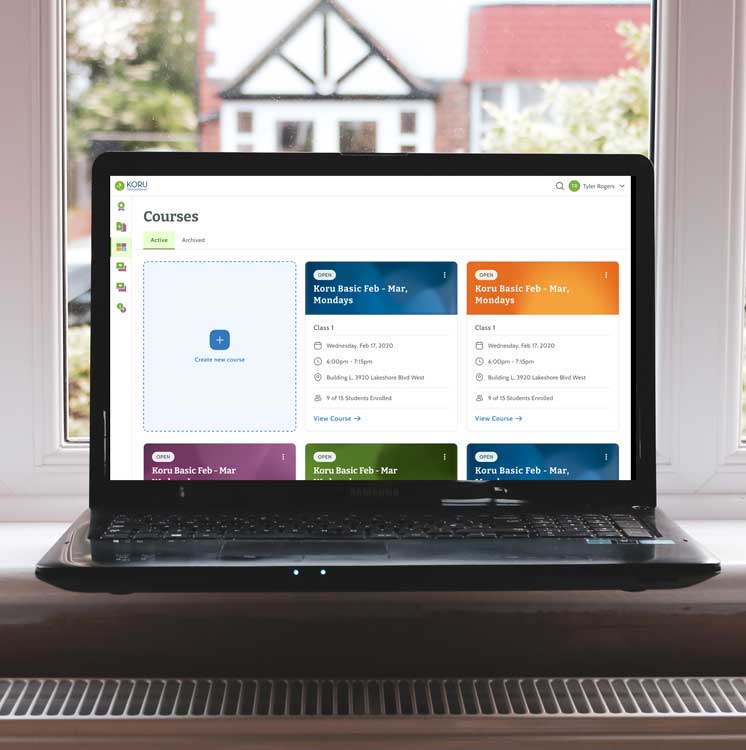

Technology Tailored to Your Needs

MIEA has developed a unique, custom-built teacher dashboard and student mobile app, designed to support the personal mentorship and one-on-one guidance essential for successful student engagement. Our technology simplifies the teaching process and enhances student engagement.

Proven Success Backed by Research

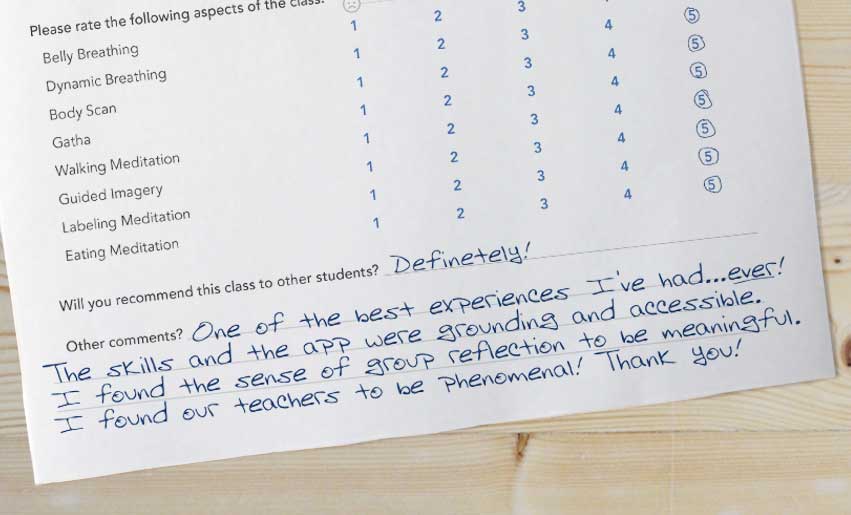

Our program’s impact speaks for itself: students report feeling more calm, experiencing improved rest, cultivating greater self-compassion, and enhancing their mindfulness.

A Mindfulness Program Designed for Emerging Adults

Unlike any other mindfulness program, the Mindfulness Institute was purposefully created for young adults. We address their unique strengths, needs, and skepticism through storytelling and metaphors. Our brief model is taught in small, diverse groups, providing structured homework and personalized mentorship.

Building Connection & Community

Connection is at the heart of our approach. Our small group and mentorship model foster meaningful connections between teachers and students, and students with their peers.

Our Story

Teaching College-Aged Adults Since 2003

With a rich history serving students at Duke University and a thriving certification program boasting over 1,000 teachers worldwide, MIEA has been at the forefront of teaching mindfulness to college students.

MIEA’s curriculum, developed by psychiatrists Dr. Holly Rogers and Dr. Margaret Maytan, emerged from their extensive experience at Duke University’s student counseling center. Through trial and refinement, and by focusing on accessibility, practicality, and immediate results, they created a class specifically designed for students and emerging adults that quickly gained popularity.

In 2013, Dr. Holly Rogers and Libby Webb founded the Mindfulness Institute for Emerging Adults, originally known as “The Center for Koru Mindfulness,” to provide training to teach MIEA’s transformative curriculum. Discover more about the reasons behind our name change and its significance to our work.

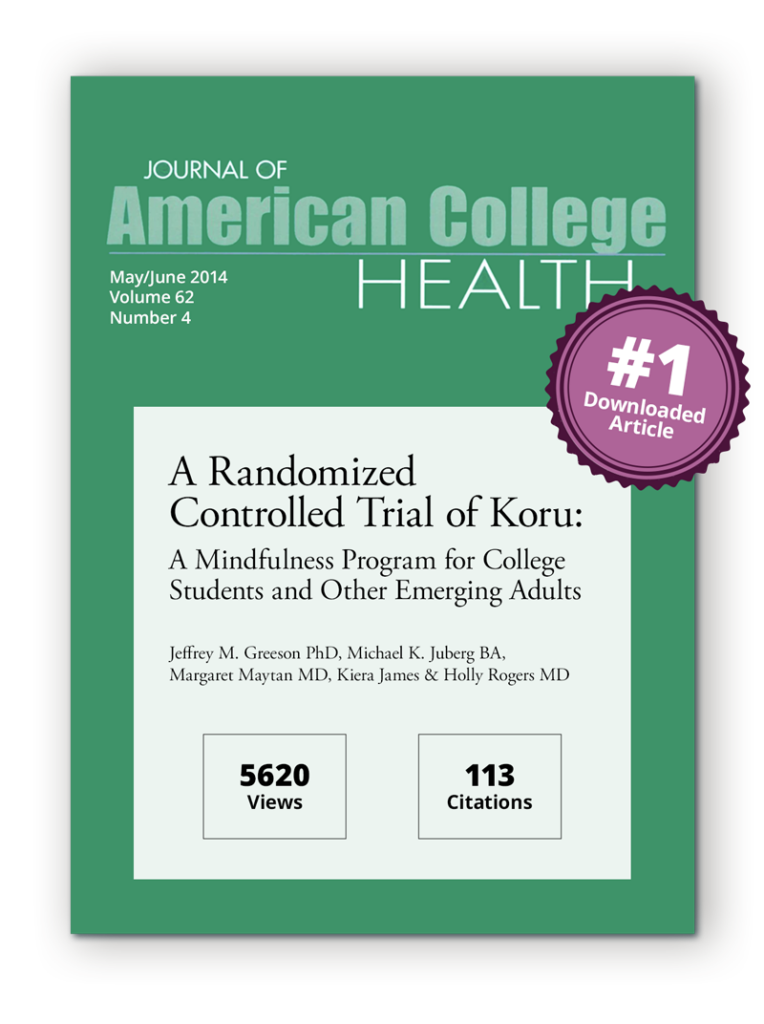

In 2014, a randomized, controlled trial confirmed the effectiveness of our curriculum, revealing reduced stress levels, improved sleep quality, and enhanced self-compassion among students. The corresponding article published in the Journal of American College Health was the most downloaded article in the journal in 2014.

Today, the Mindfulness Institute’s curriculum is taught by over 1,000 certified teachers worldwide.

Our Mission

Our mission

The Mindfulness Institute for Emerging Adults is dedicated to training individuals at colleges and universities to teach mindfulness to the emerging adults they serve, using MIEA’s evidence-based curriculum.

Our vision

We envision young adults everywhere leading joyful, meaningful lives, guided by wisdom and compassion.

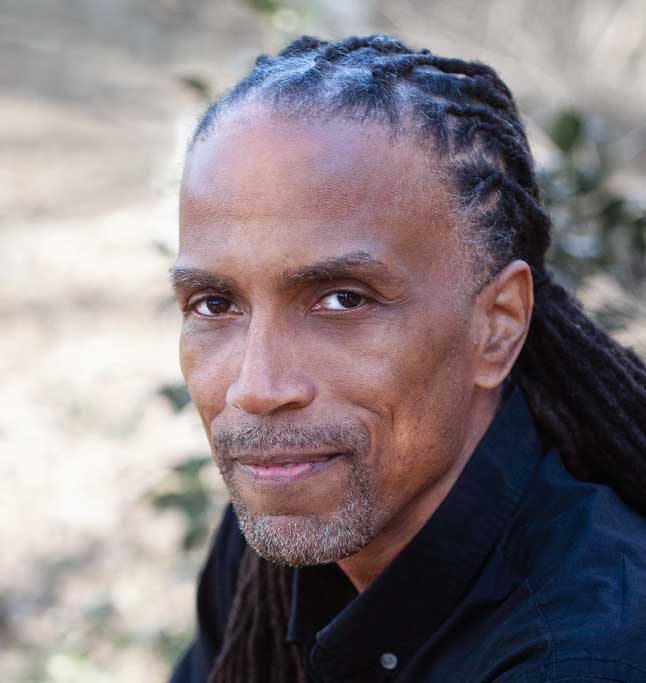

Our Dedicated Team

Co-Founder, Trainer & Author

Co-Founder & Trainer

Director of Operations & Trainer

Director of Brand & Digital Technology

Outreach & Teacher Development Coordinator

Director of Training

Asia Pacific Regional Rep & Trainer

MIEA Trainer

MIEA Trainer

MIEA Trainer

MIEA Trainer

MIEA Trainer

MIEA Trainer

MIEA Trainer

MIEA Trainer

Institutional Partners

Transforming Mindfulness Education on Campus

The Mindfulness Institute for Emerging Adults has partnered with leading campuses worldwide to transform mindfulness education for educators and students, equipping them with resilience and essential skills for success.

How MIEA is Impacting UAMS

Through evidence-based practices, customized programs, and a sense of community, MIEA is fostering a culture of well-being and resilience at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the Mindfulness Institute for Emerging Adults (MIEA)?

The Mindfulness Institute for Emerging Adults (MIEA) is the organization behind the development and certification of the Intro to Mindfulness curriculum (formerly known as Koru Mindfulness). Our institute focuses on training and certifying individuals to effectively teach this specialized curriculum.

Our curriculum is specifically designed to address the developmental needs and interests of individuals aged 18 to 29, known as emerging adults. Originating from Duke University’s student counseling center, MIEA’s curriculum has gained popularity as a highly effective program. It has undergone rigorous empirical testing through randomized, controlled trials, demonstrating significant benefits in areas such as sleep, perceived stress, mindfulness, and self-compassion.

The comprehensive curriculum comprises three components: Intro to Mindfulness, Part 1; Intro to Mindfulness, Part 2; and Intro to Mindfulness Retreat, a half-day mindfulness retreat. Intro to Mindfulness, Part 1 spans four 75-minute classes and is extensively detailed in the book “Mindfulness for the Next Generation: Helping Emerging Adults Manage Stress and Lead Healthier Lives.”.

Are you Koru Mindfulness? What happened to Koru?

Yes, we are the same organization that was previously known as the Center for Koru Mindfulness. We have recently changed our name to the Mindfulness Institute for Emerging Adults (MIEA). The change in name reflects our continued commitment to providing evidence-based mindfulness training, specifically tailored for emerging adults.

Our curriculum name has also updated to Intro to Mindfulness, Part 1, Part 2, and Retreat.

Why did we change our name from Koru to MIEA?

We made the decision to change our organization’s name for several reasons. Firstly, while we cherished the name “Koru,” we found that it did not effectively convey our role as the primary provider of evidence-based mindfulness training for emerging adults, particularly to administrators in higher education, who form our main market. We wanted a name that clearly communicated our focus on serving this specific population.

Secondly, as we continue to grow and expand, we felt that a name more aligned with our mission would support our broader development efforts. We wanted a name that did not require extensive explanation and could be easily understood, thereby facilitating our outreach and growth.

Lastly, and importantly, we considered the cultural sensitivity of our previous name. We heard concerns from teachers and students regarding the appropriateness of our use of the word “koru.” As an organization committed to inclusivity and avoiding any form of harm or discomfort, we felt the need to address these concerns and chose a name that respects cultural diversity.

Emerging adults and young adults: What’s the difference?

Emerging adulthood is the name of the developmental stage that young adults are in. It lasts from about age 18 through age 29. So essentially, emerging adults are the same as young adults, just like adolescents are the same as teenagers. Young adulthood is an exciting time of life but it also involves lots of change and lots of stress. Mindfulness is a great tool for optimizing this period of growth.

How is MIEA different from other mindfulness training programs?

The Mindfulness Institute’s curriculum was designed specifically for emerging adults and differs from mindfulness programs developed for more general populations of adults in several ways.

- Teaches mindfulness meditation as well as stress-management skills

- A brief model to accommodate the busy schedules of college-aged adults. Taught in four, weekly, 75-minute classes.

- Highly structured with daily homework of a mindfulness log and 10 minutes mindfulness practice

- Personal coaching paired with cutting-edge technology

- Taught in small, diverse groups

- Active teaching to address skepticism and build motivation

- Stories and metaphors relevant to the lives of college-aged adults

What’s the difference between Intro to Mindfulness (Koru Basic), Fundamentals, and becoming Certified?

Intro to Mindfulness (formerly known as Koru Basic) is designed for emerging adults learning basics for mindfulness and meditation. It consists of a 4-week course, with a requirement of 10 minutes a day of daily mindfulness practice.

Fundamentals is for those who want to learn more about MIEA and our curriculum and are considering whether they would like to become certified to teach the MIEA curriculum. It meets the prerequisite for our Teacher Certification. It is also useful for anyone who is wanting to learn more about mindfulness, develop their practice, and learn our curriculum. There are no prerequisites for taking Fundamentals. Please note that completing Fundamentals does not allow you to advertise as a MIEA Certified Teacher or guarantee your acceptance into the Certification Program.

Teacher Certification Training is a multi-staged process designed to teach everything needed to know to effectively teach mindfulness to emerging adults using our curriculum. The training begins with a multi-day workshop, which is then followed by online meetings and practice delivering the curriculum. When all requirements are complete, teachers in training submit a portfolio for review to achieve their certification. Once training is complete, teachers are required to pay an annual license fee to teach MIEA’s curriculum, use the trademarked Logo, and access our technology.

How much does becoming certified cost?

Fundamentals, our 5 week course that can be used as the pre-requisite for a formal mindfulness class, is $295.

Our Teacher Certification Training, the year long teacher training program, costs $1,495 – $1,795.

The Annual License Fee, which provides access to our Teacher Dashboard and course-management system, as well as other benefits, is $225/year.